Every music lover knows that warmer weather brings not only cookouts and road trips, but also the beginning of festival season. From star-studded Coachella, to our very own Sweet Life, there can be no denying the magnitude and reach of these events. However, what many attendees do not appreciate, or even acknowledge, is the history behind such festivals– the generations of producers, promoters and planners, as well as the scores of dedicated fans, who have made the festival tradition the cornerstone of the modern music industry. Even fewer consider the enormous differences between these festivals of old and those events whose fliers currently adorn every bus, billboard and backpage.

One of the most notable differences between past and present festivals is the tiered structure of new festivals– events that were once exclusively general admission are now organized as complex hierarchical structures, with different tickets going for sharply different prices. According to Rolling Stone, one of Coachella’s top VIP packages, priced at $3,250, includes a “shuttle to the side of the stage from the nearby air-conditioned safari tent, which has a couch with throw pillows, wooden flooring, a queen-size bed and electrical outlets.” The magazine adds that with this VIP package, “you’d [also] be able to drink from a private bar, use a private restroom, swim in a private pool and get advice on the next band to check out from a personal concierge.”

In comparison, even the standard VIP package for the three day event, which is advertised as “allowing access in the venue, day parking lots and the two venue VIP areas,” sold for significantly less, at $899. And even further down this undeniably classist pyramid are the masses, the average attendees without such cavernously deep pockets, who can buy general admission tickets for $375 (not including transportation).

This astronomical disparity between ticket prices is a new phenomenon, yet most attendees consider it to be a deeply entrenched reality– of course you get more if you pay more. Rolling Stone reports that the VIP pricing system developed in the early Nineties, “when stars, promoters and Ticketmaster executives created a ‘golden circle’ program for high-priced prime seats.” It was at this time that many of today’s recognizable festivals first began with this new pricing system– including Lollapalooza in 1991, Coachella in 1999 and Bonnaroo in 2002.

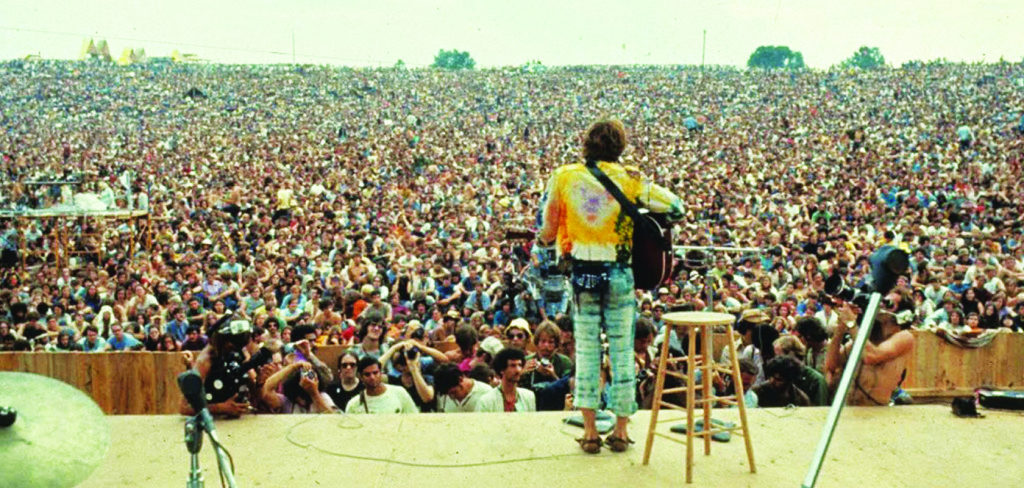

Before events like these solidified the VIP focused system, the majority of music festivals sold only single price, general admission tickets. For instance, the Woodstock Music & Art Fair of 1969– perhaps one of the best known festivals, hailed as “three days of peace and music”– sold three day tickets for $18 in advance and $24 at the gate (equivalent to $120 and $150 today). There were no VIP tents, no pristine private bathrooms or far removed viewing areas for those who could cough up enough cash. There was emphasis on community rather than commercialism.

Mr Wright, who attended Woodstock in 1969, remembers that camping at the event “wasn’t fancy. Four of us just drove up and it rained the whole time so we left early.” He adds that “the sense of community was a big deal. Those [bad] conditions brought people together. People would get up between sets and promote community.”

The value of community at music festivals may seem like a trite concept, but there can be no denying that it certainly shapes one’s experience. These aren’t always comfortable, clean events– in fact, more often than not they are marred by severe rain, resulting mud, beating sun, and technical mishaps. In the face of such inevitable imperfection, it is important to build a supportive network. Relationships that develop in the center of large crowds, to the pounding heartbeat of a good bass line, add an undeniable dimension to the festival and the general experience of music itself. Building these relationships is much harder to do when large portions of attendees are roped off.

But it’s far too idealistic to bemoan the new financial changes and subsequent loss of community without recognizing their clear purpose. At a time where music sales sink to new lows– when the idea of buying a CD is simply preposterous, and singles can be downloaded for free at the click of a button– festivals need to bring in enormous revenue for both organizers and artists to sustain the industry. It ultimately comes down to a calculated balance between cost and benefit, in which VIP ticket sales serve to alleviate potential risk. As music agent Buck Williams describes, “festivals are a huge risk to put on. Selling off sponsorships or VIP [packages] are a way to get through.”

While DC boasts a thriving music scene, in-city festivals are generally low-key affairs. However, just an hour out along I-95 is Merriweather Post Pavilion– a premier venue ranked the second best amphitheater in the country by Billboard. Merriweather offers a variety of concerts each summer, bringing together musical acts from around the world. One of the most popular events, especially among Stone Ridge students, is the SweetLife Festival. SweetLife, sponsored by sweetgreen each May, first began in 2010 and this year, for the first time, spans a full weekend, featuring big name musicians like Kendrick Lamar and The Pixies. But of course, as with all modern festivals, there is a clear class structure fostered by rampant VIP ticket sales. According to Ticketmaster, a VIP ticket at SweetLife offers access to covered seating in the General Admission Pavilion, “VIP Lounges, designated viewing areas for Main Stage and Treehouse Stage…. multiple VIP bars and private restrooms.”

However, these luxuries are not always enjoyed. Isabella Richardson ‘15 recalls her experience at the festival last year: “I ended up leaving early because I wasn’t enjoying it. [The VIP package] promised all these things– like clean bathrooms, hangout areas and food– but when I actually tried to take advantage of these benefits, everything had run out or was too crowded. Having the VIP package just made me feel kind of elitist– it just created this divide, like there were two completely separate events going on. My friend and I ended up leaving the VIP section to hang out on the General Admission lawn with our other friends. Overall, it just wasn’t worth the money I spent.”

Mckenzie Barnes ‘15 disagrees with these observations about VIP structure. She notes that “it depends on what music festival you’re going to. SweetLife is much more low-key and significantly smaller, like a regular concert, than other events across the country. Coachella meanwhile, is a huge thing where you stay overnight for several days. So it offers a lot more for VIP ticket holders, like nicer camping setups that are definitely worth the money.”

Whether you prescribe to the VIP organization or condemn it as elitist, there can be no denying that the festivals are powerful events. At the end of the day, they are about so much more than air conditioned tents, private restrooms or prime seating. The real loss in this debate is not that some ticket holders feel cheated of VIP benefits or that others feel excluded. It’s that what’s most central, most essential, about festivals is lost. They’re about that moment when a thousand voices become one, when pounding feet and throbbing bass and crackling amps tangle into a single harmony and you can feel the music.

Leave a Reply